Basics of Thermal Analysis

This introduction to the basics of thermal analysis provides an overview of material thermal behavior, key techniques, and what they reveal. It highlights a suite of methods, including differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA), thermomechanical analysis (TMA), and dilatometry (DIL). Whether it's the precise measurement of heat flow with DSC, the tracking of dynamic weight changes under temperature influence with TGA, or the analysis of evolving mechanical properties with DMA and TMA, these techniques offer a comprehensive toolkit for scientists and engineers seeking to understand material performance.

What can thermal analysis tell us?

“Thermal effects” refer to material properties that change with temperature. Temperature changes can cause a substance to transition between solid, liquid, and gaseous states, for example. These effects can occur gradually or suddenly.

Examples of gradual changes include:

- Thermal expansion (e.g., heating a steel rod causes it to expand in length)

- Weight loss (e.g., polymers often contain additives that are not chemically bonded and will escape over time when heated)

Examples of sudden changes include:

- Melting point/crystallization (e.g., phase transition of metals)

- Flame point (e.g., substances that undergo self-combustion)

- Thermally activated glueing (e.g., two-component glues)

- Glass transitions (e.g., the properties of polymers change at their glass transition)

Thermal changes are studied using thermal analysis. The principle of thermal analysis can be summarized as the “study of the relationship between a sample property and its temperature as the sample is heated or cooled in a controlled manner”.[1] The International Confederation for Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry (ICTAC) defines it more specifically: “Thermal analysis is a group of methodologies wherein a property of the specimen is quantitatively tracked as a function of time or as a response to a thermal gradient, within a precisely regulated atmospheric context. This protocol encompasses the application of a predefined thermal regimen to the specimen, which may include thermal elevation or reduction at a predetermined or variable rate, isothermal conditions, or any systematic combination of these processes.”[2]

Thermal analysis techniques

A summary of the most common thermal analysis techniques, their abbreviations, and the properties they measure is shown in the table below.[1]

Table 1: Summary of most common thermal analysis techniques.

| Abbreviation | Thermal analysis method | Measured property |

| DTA | Differential thermal analysis | Temperature difference |

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimetry | Heat flow rate difference (enthalpy) |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric analysis | Mass |

| TMA | Thermomechanical analysis | Dimension and mechanical properties (deformations) |

| DIL | Dilatometry | Length, volume |

| DMA | Dynamic mechanical analysis | Mechanical properties (moduli storage/loss) |

Differential thermal analysis and differential scanning calorimetry

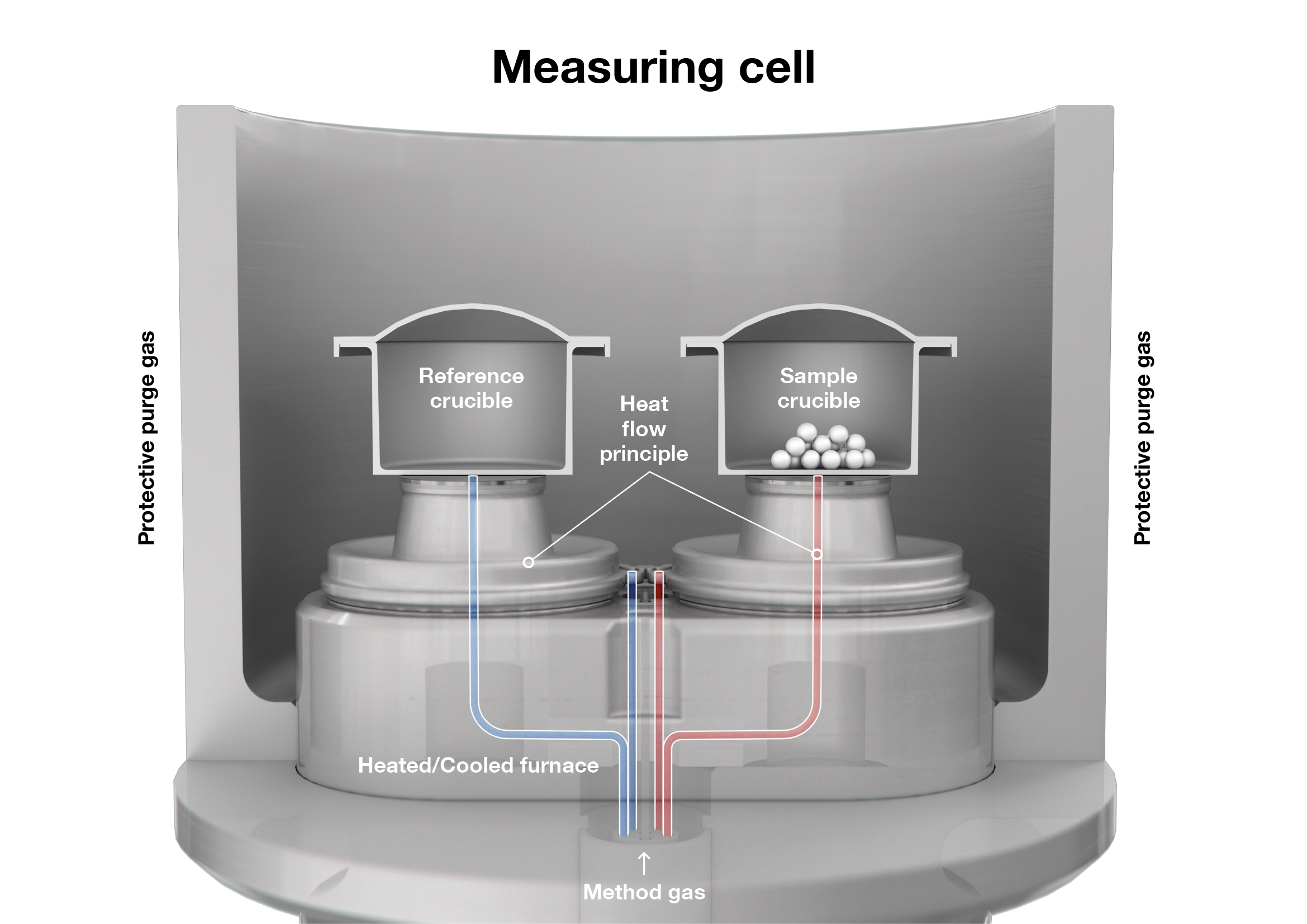

Höhne et al. define DSC as the measurement of changes in the heat-flow difference between a sample and a reference as both undergo a controlled temperature program.[3] DTA, by contrast, measures the temperature difference between a sample and a reference material. In DSC, both the sample and the reference crucible are placed on a sensor above a furnace and treated with a temperature program.

When the crucibles are heated, the temperature of the empty reference crucible increases more quickly than that of the crucible containing the sample. This is because the sample requires more energy to achieve the same temperature increase per minute, indicating a higher heat capacity. Since the two crucibles are nearly identical and the same power is supplied, the temperature difference arises solely from the sample’s thermal properties.

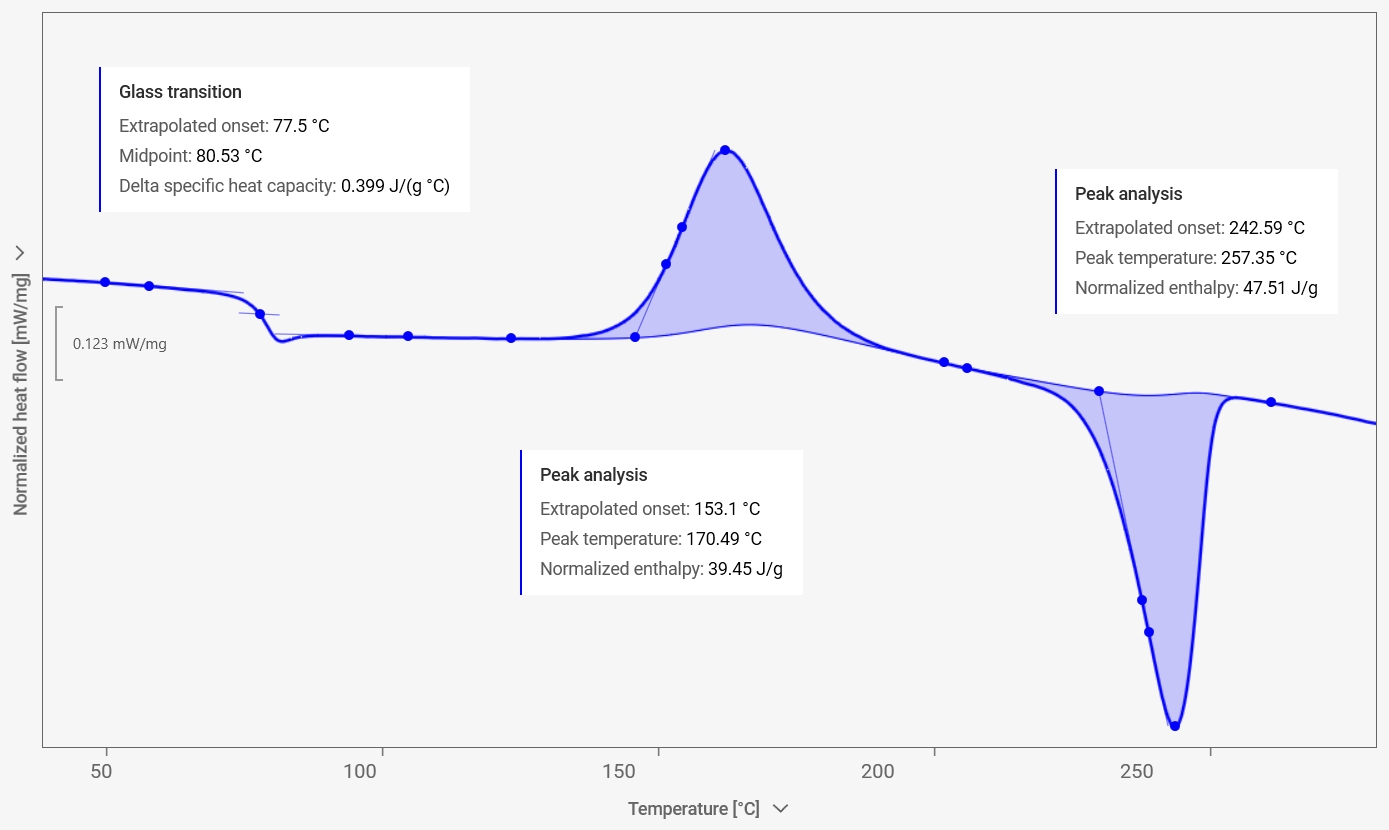

The result is a DSC curve: a graph of heat flow as a function of temperature (or time). Peaks or steps in the curve correspond to different thermal events such as melting, crystallization, glass transition, or chemical reactions like curing. By recording a DSC curve, detailed insights into a material’s properties are obtained, enabling predictions about its behavior under different temperatures. This information also supports product quality control, process optimization, and compliance with regulatory standards. Knowing the glass transition (Tg) of PET, for example, is critical, as it marks the point at which the material changes from a hard, brittle “glassy” state to a softer, more flexible “rubbery” state.

DSC devices include either power-compensated or heat-flux devices. In heat-flux DSC, the temperature difference between the sample and the reference is measured using a single furnace. The resulting heat flow is proportional to the temperature difference. Power-compensated DSC, on the other hand, uses two separate furnaces and directly measures the power needed to maintain both at the same temperature. Heat-flux DSC is robust, simple, and widely used – especially in materials science – while power-compensated DSC offers faster response times and higher sensitivity, although it is more complex and costly. The heat-flux type is by far the most commonly used in both laboratories and industry.

Thermogravimetry

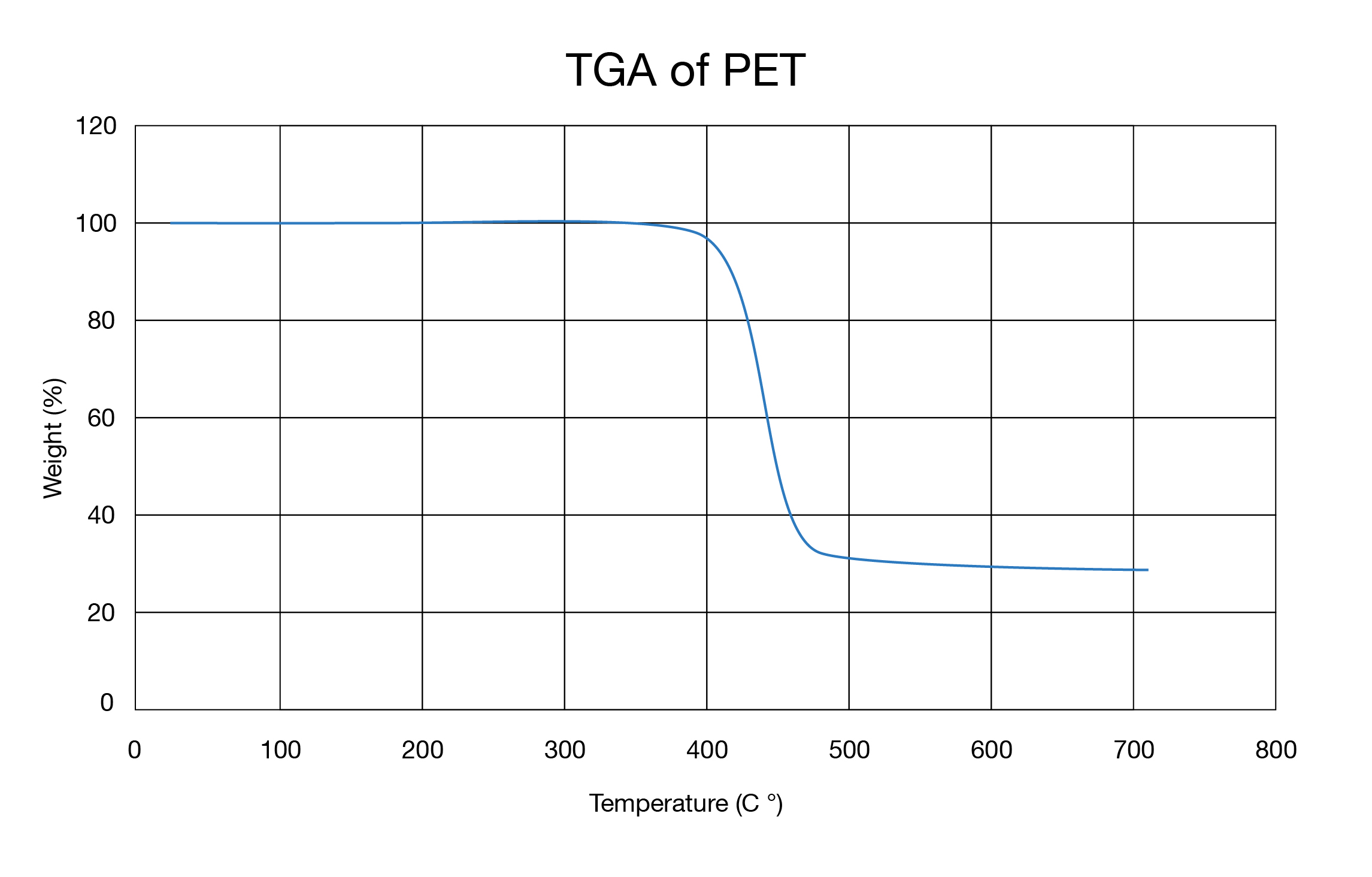

TGA studies the mass change of a sample as a function of temperature (scanning mode) or time (isothermal mode).[1] It is used to characterize the decomposition and thermal stability of materials under a variety of conditions and to examine the kinetics of the physico-chemical processes. The sample’s mass is continuously measured while the sample is heated to very high temperatures, often exceeding 1,000 °C.

A sample may gain weight during heating as it takes up chemical compounds out of the ambient atmosphere (e.g., when iron oxidizes). It may also lose weight if volatile components evaporate or if the sample starts to burn and decomposes. The gases formed during TGA experiments are often of particular interest. To identify them, TGA instruments can be combined with analytical equipment such as mass spectrometers, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry systems, or FTIR spectrometers.

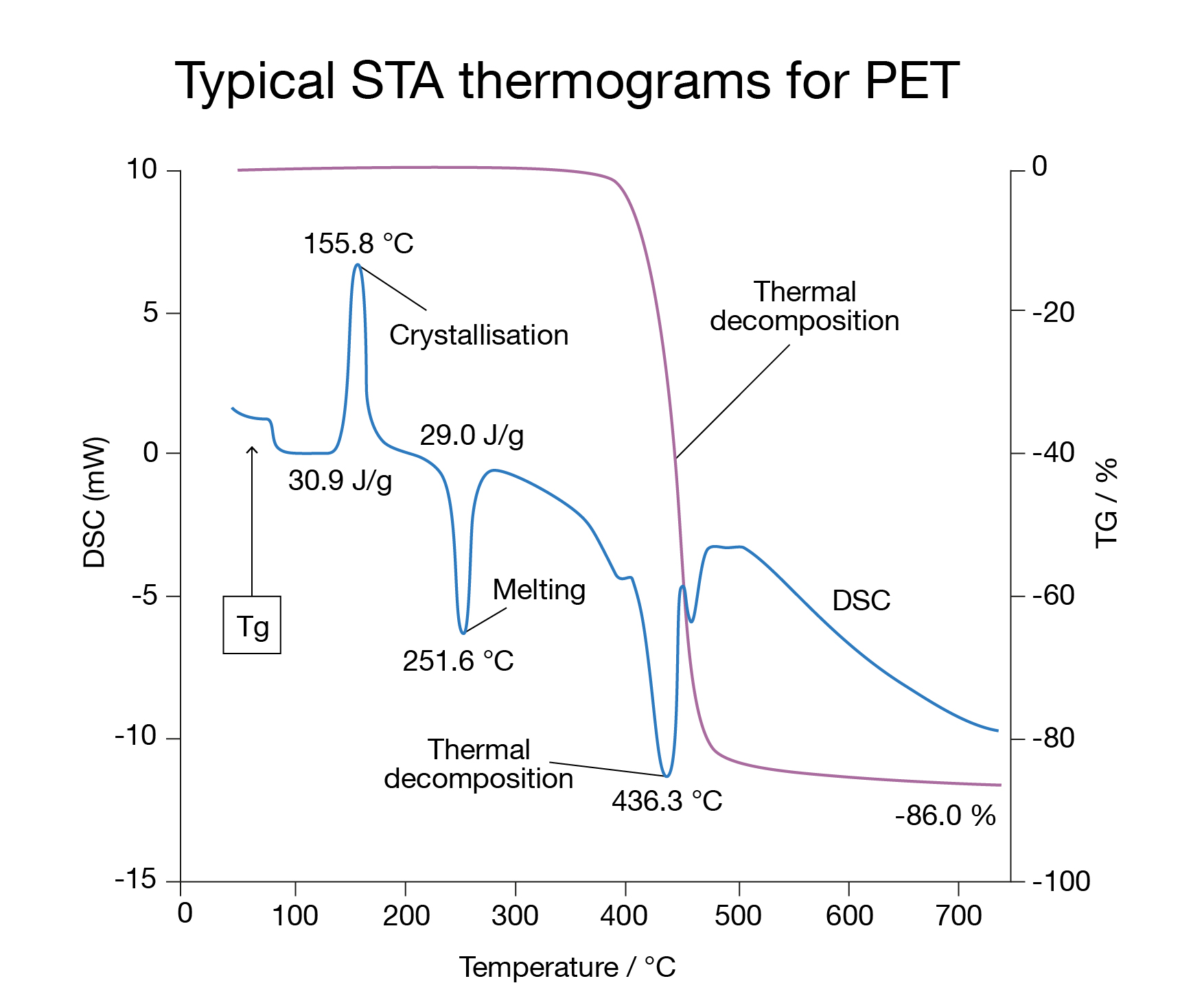

In simultaneous thermal analysis (STA), both TGA and DSC are performed using a single instrument. STA offers the advantage of saving time, as both TGA and DSC data are recorded simultaneously with accurate correlation. However, a drawback is reduced DSC sensitivity and/or resolution due to the need to combine different sensors in one instrument.[4]

Thermomechanical analysis and dilatometry

TMA and DIL provide information about dimensional changes as a function of temperature, which can be used to detect quality deficiencies and processing issues or to analyze material characteristics. While TMA can also measure the deformation of a sample, DIL is limited to detecting changes in length and volume. A small sample is mounted in the instrument and surrounded by a furnace. The variation in the sample’s geometric dimensions is recorded as a function of time or temperature.

TMA and dilatometry differ in how mechanical load is applied while the sample is being heated, but are otherwise very similar. In TMA, a force can be applied to the specimen, whereas in DIL, the specimen is kept as free of forces as possible. The most important application for TMA and DIL is the determination of the coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE), as shown in Figure 5. Other applications include the determination of the glass transition, softening point, and delamination, as well as the analysis of curing.[5]

Dynamic mechanical analysis

DMA measures the stiffness of a sample and determines its moduli and damping factor while it is subjected to minor, typically sinusoidal oscillations as a function of time or temperature. The modulus indicates how stiff a sample is. Damping is related to the amount of energy a material can absorb. Because DMA applies a periodic force to the sample and measures the response depending on the temperature, it is referred to as “dynamic.” The force can be applied through twisting, bending, stretching, or compressing the sample. This enables testing of temperature-dependent stiffness, thermal limits for use, or a blend of constituents that may be difficult to identify by DSC. For more information see Basics of Dynamic Mechanical Analysis .[5] [6]

Properties that can be determined by thermal analysis techniques

The following overview shows which technique is used to determine key parameters in thermal analysis, adapted from[7].

Table 2: Overview of applications/properties and corresponding measurement techniques. Ranking from ●●● (highly suitable) to ● (partially suitable)

| Application / Property | DSC | TGA | TMA/DIL | DMA |

| Melting | ●●● | - | - | - |

| Crystallization | ●●● | - | - | - |

| Glass transition | ●●● | - | ●●● | ●●● |

| Reaction (curing) | ●●● | ● | ●● | ●● |

| Sublimation, evaporation, dehydration | ● | ●●● | - | - |

| Absorption, adsorption | - | ●●● | - | - |

| Thermal stability, decomposition | ● | ●●● | - | - |

| Oxidative stability, decomposition | ●●● | ●●● | - | - |

| Thermal expansion and contraction | - | - | ●●● | ● |

| Thermal history | ●●● | ● | ●● | ●● |

| Specific heat capacity (cp) | ●●● | - | - | - |

| Solid-solid transitions, polymorphism | ●●● | - | - | - |

| Compositional analysis | ●●● | ●●● | - | - |

| Viscoelastic behaviour | - | - | ● | ●●● |

| Young/Shear modulus | - | - | ●●●/- | ●●●/●●● |

| Kinetic studies | ●●● | ●●● | - | - |

| Evolved gas analysis | - | ●●● | - | - |

References

[1] Lever, Trevor, Peter Haines, Jean Rouquerol, Edward L. Charsley, Paul Van Eckeren, and Donald J. Burlett. 2014. “ICTAC Nomenclature of Thermal Analysis (IUPAC Recommendations 2014).” Pure and Applied Chemistry 86(4): 545-553. doi.org/10.1515/pac-2012-0609.

[2] Wunderlich, Bernhard. 2005. Thermal Analysis of Polymeric Materials. Berlin: Springer Verlag.

[3] Höhne, G. W. H., W. F. Hemminger, and H.-J. Flammersheim. 2003. Differential Scanning Calorimetry. Berlin: Springer Verlag.

[4] Van Humbeeck, J. 1998. “Chapter 11: Simultaneous Thermal Analysis”. In Handbook of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, Vol. 1, 497-508. doi.org/10.1016/S1573-4374(98)80014-9.

[5] Ehrenstein, G. W., G. Riedel, and P. Trawiel. 2004. Thermal Analysis of Plastics: Theory and Practice. Munich: Carl Hanser Verlag.

[6] Menard, K. P. 2008. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis. A Practical Introduction. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

[7] Measurlabs. 2025. “Thermal Analysis Technique Comparison.” Accessed November 14, 2025. measurlabs.com/blog/thermal-analysis-technique-comparison.

![Figure 5: Coefficient of linear thermal expansion for PE, PP, PBT, and PA46.[5] p. 173.](https://wiki.anton-paar.com/fileadmin/wiki/images/23457_Basisc-of-Thermal-Analysis/image5.png)

![Figure 6: Tg as the maximum loss modulus G’’max and maximum loss factor tan δmax as opposed to the midpoint temperature Tmg used in step evaluation [5], p. 247.](https://wiki.anton-paar.com/fileadmin/wiki/images/23457_Basisc-of-Thermal-Analysis/image6.png)